Hypertext is a form of electronic literature that completely shatters literary classification. It incorporates various elements of literature, particularly plot and character, but some hypertext incorporates other forms of media and past literary works as well. Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl is essentially an extension of Mary Shelley’s classic novel Frankenstein: the character of the main story was created as a companion to Victor Frankenstein’s monster. However, instead of being read on a page, Patchwork Girl is a hypertext piece in which the reader has to click their way through a computer program and read lexia after lexia in an effort to piece together a jigsaw puzzle. In a lexia called Think Me, Patchwork Girl tells us that it is going to be difficult to piece the story together, but it is up to us to do so:

It is only fitting that since Patchwork Girl is made up of random body parts, the story itself will be interwoven and non-linear. Clicking one word may bring up one story path, but clicking another will bring up a different one. Putting together these pieces is not as difficult as the reader experiences the piece. However, while this is the most confusing aspect of Patchwork Girl, there is one other pre-caution I must give.

Patchwork Girl can be an extremely confusing experience, especially if the reader has had minimal contact with Frankenstein since the entirety of the hypertextual piece is an allusion to the novel. Jackson creates Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein as the character who creates Patchwork Girl. At first, this might not seem too confusing, however, once the reader comes to various parts of Patchwork Girl, particularly the journal section, the boundaries between the two literary works become rather blurred. In the lexia beauty patches, Jackson's character, Mary comments on the beauty of Patchwork Girl, but at first, the reader is unsure of whether it is Jackson commenting on her creativity or if it is Mary. Sánchez-Palencia and Almagro discuss in their 2006 article “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl,” that there are many excerpts taken directly from Frankenstein. For example, in one lexia called plea, Jackson incorporates the passage in which Victor’s monster asks him to create a female companion (plea), yet in the prelude to the story section, Jackson modifies this same passage from Frankenstein and instead changes Victor’s response so that he agrees to create a female companion:

Here begins the story of Patchwork Girl. Throughout the text, Patchwork Girl does make references to Mary, however I found it rather easy to see that Jackson meant for the reader to understand that Mary as Patchwork Girl’s creator in the story.

Throughout the entire hypertext, Patchwork Girl is on a search for her own identity. Even before she leaves for America, Patchwork Girl and Mary take patches of skin from one another’s bodies and sew them onto themselves in an effort to unite; Mary is part of Patchwork Girl, and now Patchwork Girl is now only a part of Mary. I think that this event further skews Patchwork Girl’s perception of herself, because not only is she composed of random limbs, each having a story of their own, she now has a piece of her creator within her. The lexia Am I Mary further illustrates her identity confusion:

As the reader can tell, Patchwork Girl cannot tell if these writings are purely organic from her own thoughts or if her creativity was derived from Mary. Even after she leaves for America, these thoughts invade Patchwork Girl’s mind. She went to America to find her identity as a creature separate from Mary, however she soon finds that doing so is more difficult than she first thought.

While in America, Patchwork Girl finds support from various individuals in her community. Interestingly enough, most of these people are very strange, whether it is in appearance (Chancy) or spiritual abilities (Madame Q). As the reader finds out, during her stay in Madame Q’s living quarters, she discovers that Chancy is a woman; in my experience with the story, the two girls revel in their mutual secrets:

Here, we can see that while Patchwork Girl and Chancy develop an extremely intimate relationship with one another, she is very reluctant to tell her that she does not have an individual past, but rather a collective past that she cannot call her own. Chancy continues to probe her past, however Patchwork Girl reacts badly and runs away from Chancy. This is when she beings to fall apart at the seams. In a lexia called she goes on, Madame Q says something interesting that is relevant to the subsequent events: “We are ourselves ghostly. Our whole life is a kind of haunting, the present is thronged by the figured of the past… And we are haunted, by these ghosts of the living, these invisible strangers who are ourselves” (she goes on). It seems as if the phantom pasts of all of her limbs have waged a war against Patchwork Girl, competing against each other for a spot in her collective past.

This particular screenshot features multiple instances of various body parts falling off, which terrifies Patchwork Girl. In one lexia, she literally rips a foot off of a man and sews it onto her leg in an act of terrifying desperation to pick up the pieces. It is interesting that in her mind, in order to become whole again she needs to have each limb sewn back onto her body; she cannot live with a stump for a leg, even when someone else witnesses it falling off.

Later in the hypertext, Patchwork Girl begins to think that maybe her body parts are revolting because she does not have a past and therefore seeks one out. It is clear that Madame Q’s story about phantom limbs influenced her need for a past of her own that is not comprised of multiple individuals’:

This concept must have quite been terrifying to Patchwork Girl and may have even influenced the nightmares she reported having. Since she is made up of parts, her past must be phantom limbs of all of the individuals she is comprised of. However, she misunderstood Madame Q’s point; what she meant was that everyone’s pasts are all intertwined as a collective unit: there is no individual past. But Patchwork Girl is so convinced that she needs to understand who she is as an individual that this literally tears her apart. This is where I believe the entire concept of the hypertext piece comes into play.

Just as a hypertext is a mosaic, I think that the entire theme of Patchwork Girl is that we are ourselves a mosaic but are so intent on identifying ourselves as individuals that we forget how intertwined all of our lives truly are:

Identities themselves are not contradictory. It is what and how humans show as their identity that is contradictory. As an American culture, we are so intently set upon showcasing our individuality whether it is through fashion, music, politics, what have you, but what people fail to integrate into our lives is the fact that we take bits and pieces of our friends and family members and turn them into ourselves. I have faith in humanity, like my friend Ellie, not like my friend Stephanie; I am outspoken like my friend Stephanie, but not in the way that James is; I am kind and supportive like my mother, but not in the ways some of my other friends are. The point is we are an accumulation of the individuals around us, and so is Patchwork Girl but in a more direct way. She is physically comprised of bits and pieces of the deceased, and therefore their pasts pervade her existence at every second, even while she sleeps. However, she does not have an individual past that is from one person, which I think is what drives her to buy Elsie’s past.

Much like the experience of reading Patchwork Girl and trying to piece together all of the lexia to form a collective linear story, in the end, Patchwork Girl must forget that all of her parts come from different places and need to be viewed as a whole, collective existence. As Sánchez-Palencia and Almagro (2006) also say, in order to fully understand the hypertext, the reader must piece together and interpret each lexia so that they combine to form a collective plot instead of simply being individual lexia or events that, when viewed separately from each other do not fit cohesively.

Happy Reading,

Alicia Mangiafico

(Works cited)

Sánchez-Palencia, Carolina, Almagro, Manuel. “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl.” Atlantis 28.1 (2006): 115-129. PDF.

Jackson, Shelley. Patchwork Girl. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems, 1995. CD-Rom.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Interactive Fiction: an Adventure

Playing with Interactive Fiction is one of the most fun experiences I have had with literature in a while. This may be because it is so vastly different than a story on paper, but that is one of the main reasons individuals appreciate Electronic Literature in general: it goes far beyond the page and straight into your mind. As Mary Ann Buckles tells us throughout her article “Interactive Fiction as Literature,” it encompasses mystery, adventure, science fiction, and romance (not in the love sense, but in the medieval times sense) novels. For myself, I think the most captivating of these genres is adventure because it adds an element of thrill, meaning the thrill of exploring something novel and exciting. For me, Interactive Fiction is much like an adventure novel. In a way, the forest, which characters may explore in a traditional novel, is the Inform7 program. Players must figure out the inner workings of the software program, like which specific input will give them the desired response. In order to illustrate how Interactive Fiction is like an adventure novel, we will be using Emily Short’s Galatea as an example.

Galatea is a relatively short game, running as few as ten minutes, but as long as about 45 depending on how in-depth you want to go. Throughout the game, the player must converse with Galatea, inquiring about her creator and her own ideas and experiences about the world. For example, after reading the placard telling about Galatea as a statue, the player might consider asking about the artist, Pygmalion:

In order to get a response from Galatea, one must type “ask about Pygmalion” or “a artist.” The nice thing about Interactive Fiction is that within one question, the reader can get information about a character that might take reading chapters and chapters of a book to find out. Although we never directly meet Pygmalion in this IF game (called “other person”), just by asking about him we can understand a lot about him and his relationship with Galatea: we find out that he regretted creating Galatea once she awoke, had nightmares, and drank often. This especially applies to the non-player character (NPC) Galatea. By empathizing with her, being patient, and gaining her trust, she reveals more personal information. It was particularly difficult to get her to confess her love for her artist, but by being patient and listening to what she has to say (by typing “z”), the player will be able to hear her story:

Unfortunately, in this particular cycle of the game, I was unable to continue asking questions because finding out about Galatea’s love for Pygmalion was the ultimate goal of the game.

It is interesting that finding out about Galatea’s love for her creator elicited the most direct ending to this piece of Interactive Fiction. Most of my other experiences with Galatea always ended in a very similar way: she seemed to become disinterested in the conversation, particularly after being asked too often about the same topic:

I found that carrying out a conversation with Galatea was often extremely difficult, particularly if I wanted to find out more about a topic. According to Fredrik Ramsberg in the article “A Beginner’s Guide to Playing Interactive Fiction,” he gives the reader a list of verbs that are common to IF games, particularly ones that apply to conversation, such as “Tell [blank] about” or “ask [blank] about” (Ramsberg, “A Beginner’s Guide to Playing Interactive Fiction). However, in my experience with Galatea, the “telling” action did not work well when I used it:

When used, I would often get a message that said “you don’t have much to say about that” or “you’d rather hear what she has to said about it.” However, I found out that the “think about” action is much more effective. Instead of only receiving the “you don’t have much to say about that” output, the conversation would continue and the player-character would actually participate in the conversation instead of jumping from topic to topic with each input:

Unfortunately it took me about three plays to notice that there must have been some other way to interact with Galatea that included my player-character actually conversing with her, so I had to look up other users’ experiences with the game. While I was looking this up, I came across a page by Emily Short called “Cheats and Walkthroughs” that gave me a command that would show conversation statistics. By using this command, a top bar would appear and tell the player what mood Galatea was in, what the current and next conversations are, the amount of sympathy she was feeling for you, as well as if there is any tension. This was certainly one element that I really appreciated. It acted as a guiding tool for what I might ask about next or what I should avoid. For example, her mood became “scary” the more we spoke about the Gods, and “happy” the more we spoke about Pygmalion and his travels. It was interesting to see how the mood element played into the conversation and how sympathetic she became. This particular element of the story truly made me understand Galatea’s experiences. You can tell just by the variability of her mood that her story is going to be rocky but beautiful at the same time. Even though some players claim that her she is too touchy as a NPC, I disagree. Her mood variability adds an element of adventure and suspense, especially if you do not want to upset her. Clearly it must have been extremely difficult to create such a real character, from my own experience creating Interactive Fiction I found it most difficult to create characters that acted more like a real person than most NPCs.

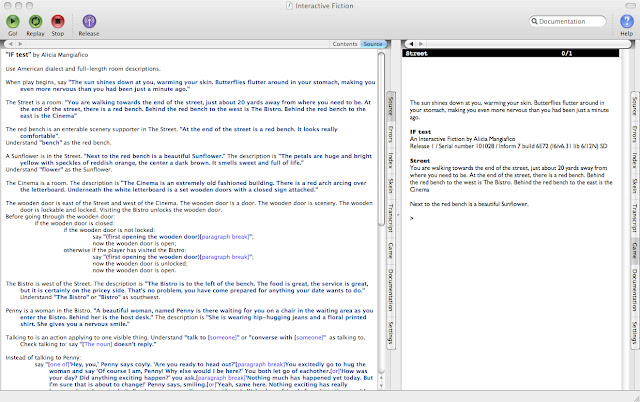

It was truly an adventure playing Galatea, both getting to know her and understanding how to manipulate the conversation so that it was maintained over time. Writing my own IF was even more of an adventure, though. The original idea I had for my Interactive Fiction was based around a first date between two friends who have had intense feelings for one another for quite some time. The player took the role of the male taking out his friend, Penny. The player starts off on the street and has the choice of picking one of three flowers next to a bench; later in the story the player can choose whether or not he/she would like to give Penny one of the flowers. I had so much fun with the idea of playing out the endless possibilities of the date. I felt like I was creating this whole new world in which anything could happen; I felt like I was the author of some awesome adventure. In this way, I think that IF allows the author more room for creativity because you can play with the many different ways in which a conversation or event can play out in a world entirely of your own creation.

The endless amount of creativity also was extremely frustrating. When I started to make the Cinema, I realized how difficult it was going to be to tell the program that the cinema was only available after the player went to the Bistro. Once I believed I finally figured out how to do this by creating an un-lockable door, I was so relieved:

One aspect of my IF piece I was very happy to have been able to program was taking and giving flowers to Penny. I was able to successfully program Inform7 to say different things according to which flower the player choose to take and give to Penny. Unfortunately, I was not able to locate a screenshot of this part of my creative process.

Simply the prospect of endless possibilities sets Interactive Fiction apart from traditional literature. Unfortunately, I think that the inexperienced players of IF do not know how many paths they can take as a user. When I played my very first IF, All Roads, I thought it was pointless and too overtly like a puzzle. I did not feel like I was free to make any decision that I wanted because I knew it was only going to come to the same conclusion. However, with Galatea and Whom the Telling Changed, I found that I had much more leeway as a player because I could manipulate the story as I saw fit, just as I did with Galatea. This plays into the creative possibilities as a creator of IF as well. Now that I have had some experience with writing IF, I know some of the basics of programming Inform7 and therefore understand how to manipulate the storyline. Simply knowing all of the conversation topics and ways to interact within the IF world really impacted game play. When I first played Galatea I was frustrated by her coldness during conversation and thought that she was a very simple character, which was not very impressive. However, when I started writing, I realized that there were more possibilities to the conversation and understood what to use as input and how to empathize with Galatea as a piece of art.

All in all, I had a great experience with Interactive Fiction, but readers must understand that certain pieces may be less fun to interact with than others; some IF games are more obviously a puzzle, like All Roads, while some games have characters that are puzzles themselves, like Galatea. Being patient and knowing that IF as a whole is an adventure in and of itself will certainly enhance your experience with it.

Happy Gaming,

Alicia Mangiafico

Works Cited

Buckles, Mary Ann. “Interactive Fiction as Literature.” October 13 2010. <http://www.malinche.net/interactivefictionasliterature.html>

Ingold, Jon. All Roads. <http://collection.eliterature.org/1/works/ingold__all_roads.html>

Jerz, Dennis G. “What is Interactive Fiction” Dennis G. Jerz. October 6, 2010.

Ramsberg, Fredrik "A Beginner's Guide to Playing Interactive Fiction." October 6,

2010. <http://IFGuide.ramsberg.net>

Reed, Aaron A. Whom the Telling Changed.

reed__whom_the_telling_changed.html

Short, E. “Cheats and Walkthroughs” 2000. November 1 2010.

<http://emshort.home.mindspring.com/cheats.htm>

Short, E. Galatea. <http://collection.eliterature.org/1/works/short__galatea.html>

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Experiencing Electronic Poetry: What It is, What It is not, and How to Understand It.

Experiencing all of the elements of electronic literature can be quite a frustrating experience. Some pieces are complicated and time consuming to understand while others are easy to read and interact with. The ease of reading varies depending on the number of elements the author chooses to incorporate within the piece. Since there are so many elements exposed to the reader at the same time, it is important to understand how each affect one another. The most obvious of these are sounds, images, interaction, text, and of course the effect the piece has on its reader.

Since electronic poetry is such a young form of artistic expression, many scholars are attempting to define what it actually is and what it constitutes. According to The Electronic Literature Organization, the definition of electronic literature is: “work with an important literary aspect that takes advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand alone or networked computer” (http://www.eliterature.org/about). However, because it is such a new form of literature, it “tests the boundaries of the literary and challenges us to re-think our assumptions of what literature can do and be” according to Katherine N. Hayles in her article “Electronic Literature: What Is It?.” As a novice reader of electronic literature, I have only been exposed to poetry on the page, so I thought it might be a good idea to start with explaining what electronic poetry is not.

When you first venture to Goldsmith’s “Soliloquy,” you are faced with a screen that allows you to choose which day you would like to explore along with the hour of that day. That page then transforms to blankness, where the only words you see are “Hi” and the day options at the top of the page. Next, the reader must interact with the piece in order to find what else the poem says. If the reader were to run their mouse around the center area of the window, they would find that some words appear underneath the area the mouse is. These sentences of words that appear may not seem to have any sort of meaning. In the case of my interactions with the poem, the line that appears says “yeah but I mean, I want to take her for a walk, you know, I take her up to Washington Square, you know, she’s been pretty cooped up for the last few days.” The reader can infer that the author is speaking either about a dog or a person that he is about to go for a walk with. In order to get the full experience however, the reader must highlight the entire screen so that they can read what the author has said in the correct sequence. Once the reader has read the page, they will understand that all Soliloquy is is a transcript of the author’s spoken words throughout an entire week.

This electronic poem has only a few essential elements that are considered part of e-poetry. The effects Goldsmith used in creating this poem are primarily based on interaction. The user must run their mouse over the words of the poem in order to unveil what it says. Unfortunately, the only way in which this piece provokes thought is that the reader must figure out how to read the rest of the poem. The reader is faced with the choice of running the mouse over each line one by one, or they could utilize their knowledge of computers in that if you highlight the entire page, you can see all of the text. The actual content of this “poem” is simply the spoken word of the author. Spoken word in and of itself is not essentially creative. In fact, a good chunk of this poem is the author saying “okay” or arguing with whomever he is having a conversation with. The author is an artist, and one would suspect that in everyday conversation he may naturally craft his words in a way that is poetic, but my experience with this poem was entirely mundane and non-poetic. Goldsmith’s statement with this piece may have been that simply everyday conversation is beautiful and always thought out, but the words he transcribed did not seem well thought out at all. In fact they seemed jumbled and frantic. Therefore, according to the Electronic Literature Organization’s standards as well as Katherine Hayles’ and Memmott's, Goldsmith’s poetic work is not electronic poetry. The interactions and words on the screen were not sufficient enough to cause thought (Memmott, 303), in my opinion.

After reading the words on the screen, the reader is then faced with a decision: is this a beautifully simplistic poem, or is there something more complicated going on here?

When I interacted with the poem, I decided to copy and paste all of the characters that were illegible. When I pasted these characters into word, I found out that they were word-soup: all of the words were stuck together with no spaces in between. Some of the sentences were cut off in the middle.

As the reader tries to decipher what the author is saying, they will come across random thought-inspiring phrases or ‘sentences’ if you will. For example, if you continue reading, you will come across this sentence “stepfartherandattempttobringtolightthelargelyunconsciousinnerbiograph.” What makes this piece extraordinary is the finding that there are citations inserted throughout the page. This is extremely important for the artist’s statement. Quite simply put, her point is that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The way you choose to interact with “Beauty Fiction” also plays on the idea of beauty. You can either read the words that are clear and in your face and accept them as the most beautiful part of the piece, essentially holding the belief that beauty is simple something that you can see within an instant. Or, you can further examine the piece by taking the time and consideration to read the miniscule font, the details of the piece and find that “Beauty Fiction” is much more profound than you had initially thought. If this poem were simply on a page, I do not think this point would have been nearly as clear is it was in its interactive, electronic format.

It is clear that Nari’s statement with “Beauty Fiction” is that everyone has a different perspective on beauty. She utilizes a vast amount of authors’ perspectives on beauty or beautiful experiences to tell the reader that yes, simple events are beautiful, but the ones that the most exquisite are the those that vary between person to person, whether it be bodies, thoughts, experiences, or the love they share for each other. That is why “Beauty Fiction” can be considered a piece of electronic poetry while Goldman’s “Soliloquy” cannot. You must choose how to navigate the poem, and depending on the way in which you interact with the poem, you will still have a thought-provoking experience, regardless of the lack of other electronic elements such as sound.

The experience of creating a piece of electronic poetry can be just as frustrating as interacting with a published work. As Memmott tells us, “similar to a theater performance, a digital poem is a language that must be read holistically for all the technologies and methods of signification at play” (303). As a student just beginning to learn about the creative powers of Powerpoint, I was and still am overwhelmed at the amount of choice I have when selecting ways in which I can emphasize my words. There are so many elements to the Powerpoint program that can incorporate interaction, sound, images, etc… that I am often stuck trying to figure out which option is best for what I am trying to convey to the reader. However, I truly enjoy being able to use specific effects to emphasize certain words and ideas I find most meaningful to convey to my reader.

Creating my own piece of electronic poetry made me respect electronic poetry artists simply for the fact that they are often creating the programs that they work with themselves. They are always trying to find new, innovative ways to accent their ideas, which must be incredibly difficult to do in this evolving form of artistic expression. It is very easy to critique a piece when you do not understand the inner workings of the poetry and only understand the words that the author is writing you. When I create a piece of poetry, I find that the words flow somewhat easily from my brain to the page, for others it is not as easy. But I think that when an individual really looks through the words and into the inner workings of a piece of electronic poetry, listening to the sounds, examining the images paired with the piece, or exploring the different ways they can interact with it, they can see the true beauty of the work, just like Nari conveys in her poem “Beauty Fiction.” In short, whether you are a novice or expert electronic poetry reader, the best way to understand a piece is to navigate, interact, absorb, and be patient with the work you are looking at.

Works Cited:

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Soliloquy. <http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/goldsmith/soliloquy/>.

Hayles, Katherine N.. Electronic LIterature: What is It?. The Electronic Literature Organization, 2 Jan. 2007. Web. 1 October 2009. <http://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html>.

Larson, Deena. A Quick Buzz Around the Universe of Electronic Poetry. <http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/currents/fall01/buzz.html>.

Memmott, Talan. Beyond Taxonomy: Digital Poetics and the Problem of Reading. <talanmemmott.com/pdf/TALAN_MEMMOTTcv.pdf>.

Nari. Beauty Fiction. <warnell.com/real/beauty.htm>.

Good luck,

Alicia Mangiafico

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)